By Syeda Mamoona Rubab

Syeda Mamoona Rubab is not surprised by the ruling which came out on Wednesday

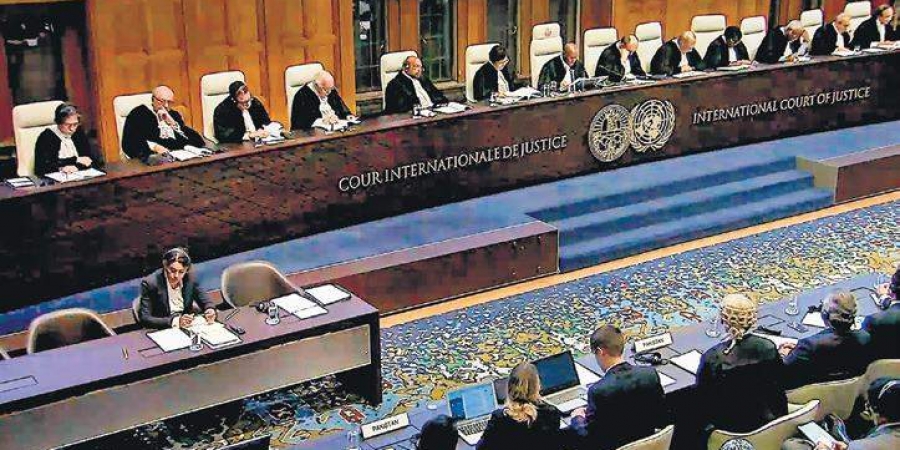

The International Court of Justice has ruled in favour of consular access for the Indian spy, Commander Kulbhushan Jhadav, who is on death row in Pakistan. Yet the verdict by no means provides plain victory for India, which was seeking a clear strike down of capital punishment awarded by the military tribunal.

The international court, in its ruling issued at the Hague, stated: “Pakistan must inform Mr Jhadav without further delay of his rights under Article 36, paragraph 1(b), and allow Indian consular officers to have access to him and to arrange for his legal representation.”

Furthermore, the court ruled that Pakistan must provide effective “review and reconsideration of the conviction and sentence of Mr Jhadav.”

India immediately celebrated it as a victory with Prime Minister Narendra Modi attempting to lead the narrative by tweeting: “We welcome today’s verdict. Truth and justice have prevailed. Congratulations to the ICJ for a verdict based on extensive study of facts. I am sure Kulbhushan Jadhav will get justice. Our government will always work for the safety and welfare of every Indian.”

Pakistan’s Foreign Office clarified that since the ICJ judgment decided not to acquit and release him, it implied rejection of the Indian prayer.

To fully understand the verdict, it is important to keep India’s prayer before the court in perspective. India had following the death penalty for Jhadav by Army’s Field General Court Martial (FGCM) over espionage in April 2017 and it rushed to the United Nation’s judicial organ claiming that Pakistan had violated the 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations by not providing it consular access to Jhadav immediately after his detention.

Delhi initially sought preliminary measures staying his execution, which were granted by the court. The main prayer of the Indian case, however, was that denial of consular access could be remedied by ICJ by “at least” ordering Jadhav’s acquittal, release and return to India.

The issue of jurisdiction was, moreover, settled along with the decision about the admissibility of the case in May 2017, when the court assumed jurisdiction on the grounds that both India and Pakistan were signatories to the Optional Protocol to VCCR, whose Article 1 provided it compulsory jurisdiction in disputes related to implementation of international treaties.

The issue at the heart of the international litigation initiated by India was, therefore, the denial of consular access to Jhadav under Article 36, paragraph 1 (b) of VCCR – the international treaty guaranteeing people the right to contact their diplomatic mission for assistance when detained on a foreign land.

The verdict is consistent with the precedents in three similar cases brought before ICJ over denial of consular access and in all three instances the court had ordered provision of consular access. Pakistan’s position in the case, however, remained that under international law, spies are not entitled to avail consular access facility; there was incontrovertible evidence in shape of the passport issued to him in the name of Mubarak Hussain Patel that he was on an undercover mission.

Those contentions notwithstanding, the court seemed to be convinced that as per the treaty, consular access kicks in immediately after detention of a foreigner without any exception.

India, probably for its domestic political reasons, had asked for a bit too much by bringing up the ICCPR and the lawfulness of military trials. It must not be forgotten that ICJ has a very limited jurisdiction when it comes to relief. ICJ could not have ruled on these issues.

The court could have only asked Pakistan to “review or reconsider” Jhadhav’s conviction and sentence in accordance with Pakistan’s own laws, which it did.

“The court finds that Pakistan is under an obligation to provide, by means of its own choosing, effective review and reconsideration of the conviction and sentence of M. Jhadav, so as to ensure that full weight is given to the effect of the violation of the rights set forth in Article 36 of the Vienna Convention, taking account of paragraphs 139, 145 and 146 of this judgment,” the court ruled.

In all of the ICJ’s previous decisions concerning Article 36 of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations 1963 (which involved death sentences imposed by the USA), the court made it clear that it was not a court of criminal appeal and the presence of “effective” “review and reconsideration” by domestic courts was an appropriate remedy, even if a breach of the right to consular access had been established.

Pakistan’s government has rightfully expressed its willingness to implement ICJ’s verdict as a civilised country. Islamabad realistically has no other options. Disregarding the order now would not only be legally, but also politically and diplomatically costly for Pakistan. The ICJ has powers to refer cases where states don’t comply with its orders to the Security Council for action. US did not implement verdicts in both cases in which ICJ ruled against it for denying consular access. But, US is in another league.

It has been Pakistan’s position at the UN that ICJ decisions must be implemented. Just last December, Pakistan voted in favour of resolution moved by Mexico at the UN General Assembly entitled ‘Judgment of the International Court of Justice of 31 March 2004 Concerning Avena and Other Mexican Nationals: Need for Immediate Compliance.’

Pakistan could have, however, made the verdict look more favourable by granting consular access to Jhadav, even after India had moved ICJ, and gone ahead with the civilian review process. Doing so would not have materially changed the ground situation, but it could have shown Pakistan’s “good faith” and had some impact on the final verdict.

The writer is a senior researcher at Islamabad Policy Institute. She can be reached at mamoona.rubab@ipi.org.pk