On September 24, 2025, following North Korea and Russia, India launched its new missile force by testing Agni Prime from a rail-based mobile launcher. According to India’s Defence Minister Rajnath Singh on X, “this successful flight test has put India in the group of select nations having capabilities that have developed canisterised launch system from on the move rail network.” This development places India alongside North Korea and Russia. The recent consecutive missile tests and ongoing threats of the continuation of Operation Sindoor by Indian military personnel and politicians – after the India’s defeat in the India-Pakistan four-day military confrontation in May 2025 – have reignited fears of renewed Indian military escalation and adventurism in the region.

India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) confirmed the Agni Prime test from a rail-based mobile launcher system. According to DRDO, the test was conducted in coordination with India’s Strategic Forces Command (SFC). The missile was integrated into a modified rail boxcar equipped with an extendable platform designed to elevate the launcher above overhead electrical wires – a feature noted by several observers and critics. This level of engineering shows India’s intent to make its deterrent forces mobile, concealed, and survivable. The Agni-Prime also known as Agni-P, is intended for a range between 1,000 and 2,000 kilometers, approximately around 621 to 1,243 miles. DRDO stated that the missile is also deployable from road-mobile launchers. It remains unclear whether Agni-P will replace or supplement earlier Agni-series missiles such as Agni-I with a range of 700 kilometers, and Agni-II, with a range of 2,000 kilometers. The rail-based version comprises a containerized Agni-P missile, an autonomous launch capability, advance communication systems, and undisclosed safety characteristics. However, this technology also increases the complexity of tracking and verification.

For clarity, India is not the first country to test a missile from a rail-base launcher. In the midst of Cold War, the erstwhile Soviet Union tested a rail-based intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), known as the RT-23 Molodets. Russia later sought to revive this technology through the Barguzin project but eventually abandoned it to concentrate on the Avangard hypersonic missile. Later, North Korea introduced the “railway mobile missile system,” in September 2021 with India now joining the list of states pursuing rail-based missile systems.

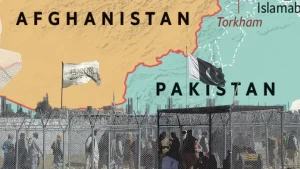

At a glance, the rail-based launcher provides Indian with an extensive operational area, roughly 40,000 miles of railway network across the country. This enables missiles to be launched promptly from any location within a 2,000 km radius, while being disguised as regular passenger wagons. It may become difficult for Pakistan to identify, monitor, and intercept these systems, such as in the 11.2 km long tunnel of Pir Panjal in Indian-administered Kashmir. The rail tunnels may provide shelters or bunkers for these missile launchers in times of conflict. It will be harder to counter them, increasing the survivability rate of these missiles. These features shorten decision time and increase the risk of escalation and miscalculation, putting the regional peace at risk. Additionally, the Agni-P can reach deep into Pakistan with a maximum range of about 2,000 kilometers. Rail mobility multiplies the number of possible launch positions and targets inside Pakistan.

On the contrary, Pakistan has always emphasized restraint and shown a responsible management of its conventional and nuclear forces. For example, the recent introduction of the Pakistan’s Army Rocket Force Command is a step toward a clearer force structure and mission separation. That command aims to separate conventional and nuclear roles by reducing ambiguity, which could eliminate chances of miscalculations or crisis escalation in the region.

However, India has, a mixed record on technology, deployment and safety. Incidents such as the BrahMos malfunction in March 2022 and other military accidents have revealed risks in deployment and training. Moreover, India’s recent stress on compellence, using the show of force to coerce its neighbour’s behaviour, results in regional and global tension. Compellence strategies can undermine deterrence logic if applied recklessly. The result is peril for Pakistan, the neighbourhood, and the wider international community. For stability, states must choose restraint and clarity over coercion.

In fact, India is now fabricating the continuation of Operation Sindoor for future wars. The test of Agni-P is one link in the recent chain of missile tests. Defence Minister Singh’s statements signal faster tri-service integration and real-time Command, Control, Computer, Communications, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (C4ISR), thereby raising the risk of military escalation for Pakistan. For Pakistan, Indian military technological advancements such as Agni-P shorten decision cycles and increase the speed of Indian coercive options. Such advancements pose a threat of crisis escalation in the near future.

In conclusion, the Agni-P test mirrors India’s rising interest of advanced delivery systems while underestimating the fragile geographical realities and security conditions of South Asia. The timing of the Agni Prime test – just months after the conflict – suggests the threat of renewed Indian hostility. In such circumstances, political and diplomatic engagements are essential to reduce tensions. At the same time, confidence-building measures are essential to minimize inadvertent escalation and risk of misperception. A few practical steps could help reduce entanglement risks. First, India and Pakistan could negotiate a mutual pledge to avoid offensive strikes against clearly identified strategic bases during peacetime, thereby preventing civilian casualties. Second, both sides could exchange technical data about launcher types, range bands, and payload options. Such transparency would reduce dangerous ambiguity in the future. Third, India could also establish a distinct command to separate nuclear and conventional systems. Clear separation would make the entanglement of conventional and nuclear systems less likely and thus lower the chances of inadvertent escalation.