In early November, Pakistan initiated its most significant higher defence restructuring in nearly five decades. Through a constitutional amendment and later changes to relevant military legislation, the office of the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (CJCSC) is being abolished, and a new position of Commander of Defence Forces (CDF), who will also serve as Chief of Army Staff (COAS), is being introduced. This dual role raises critical questions: What is the scope of this restructuring? How will it reshape the authority and autonomy of the navy, air force, and nuclear forces? Will the consolidation of command under CDF-COAS foster the promised “synergy,” or reinforce centralisation as critics warn? The answers will define civil-military relations and inter-service dynamics for years to come.

A brief history of Pakistan’s Higher Defence Organisation

At independence, Pakistan inherited the Higher Defence Organisation (HDO) of the British Raj, where the Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the British Indian Army reported to the Viceroy of India, while the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force remained under Army Headquarters. The C-in-C was always an army officer, reflecting the army’s size and its role in supplying manpower for British campaigns across Asia and Indo-China. Pakistan received roughly one-third of the British Indian Army, and British officers continued to command its forces for four years, entrenching colonial-era HDO practices.

In 1951, General Ayub became the first native C-in-C and granted autonomous status to the Navy and Air Force. A Joint Chiefs Committee (JCC) was created for coordination, later upgraded to the Joint Chiefs Secretariat (JCS) with the Army C-in-C as its moderator. Ayub’s appointment as Defence Minister in 1954 reinforced the Army’s primacy. Yet, the JCS failed to mature into a strong joint body, as service headquarters retained autonomy in planning, force development, and procurement. The 1965 and 1971 wars highlighted the limits of this model, as naval and air force leadership remained secondary in wartime decision-making.

Reform efforts began in 1972, converting the C-in-C roles into Chiefs of Staff in 1973. In 1976, the Bhutto government upgraded JCS into Joint Staff Headquarters (JSHQ) to institutionalise ‘jointness,’ introducing a permanent chairman, i.e., CJCSC to be rotated among the service chiefs. The CJCSC became the senior-most officer and the principal military advisor to the government during war. Before the JSHQ could consolidate, General Zia imposed Martial Law, centralising authority in the COAS office, which he also held as president of the country. Since then, the COAS has remained the dominant military advisor, while naval and air chiefs focused on respective force development and administration. By 2022, the COAS was leading tri-service talks with China on defence cooperation.

This arrangement persisted even as successive governments adhered to the 1976 framework, appointing CJCSC largely in form. Rotation was often ignored; in 1999, a naval chief resigned when Gen Musharraf was made CJCSC while simultaneously serving as COAS. Gradually, the CJCSC office and JSHQ came to perform three roles: coordinating planning through JSHQ, leading military diplomacy, and overseeing nuclear policy post-1998 tests. The latter was formalised under the National Command Authority (NCA) Act, 2010, delegating authority to CJCSC and Director General Strategic Plans Division (SPD). The CJCSC also served as deputy chairman of the Development Control Committee, guiding technical aspects of weapons and command systems.

HDO Restructuring 2025: COAS-CDF & Commander NSC

Nearly six months after the limited conflict with India, the federal government moved to abolish the office of the CJCSC and elevate the COAS to a dual role as CDF. This restructuring transfers two core functions of CJCSC i.e., coordination and military diplomacy to the COAS-CDF, while creating a new position of Commander National Strategic Command (CNSC) to oversee nuclear forces. The empowered COAS-CDF will assume responsibilities akin to the former C-in-C of the British Indian Army: directing war strategy, planning, operations, force development, procurement, induction of new systems, and budgetary control, while serving as the prime minister’s principal military advisor. The JSHQ is expected to undergo an organisational upgrade, integrating relevant offices from service headquarters to form a centralised defence staff. The naval and air chiefs, along with a possible vice-COAS, will manage administration and training, while strategy and planning will originate from CDF headquarters.

Meanwhile, the nuclear managerial role of the CJCSC is being shifted to a newly created CNSC. The NSC will unify the three services’ strategic commands under a single four-star army general, appointed by the prime minister on the recommendation of COAS-CDF. With this change, the future role of the SPD within this new structure remains critical, as it continues to drive development and management of strategic nuclear deterrent and Pakistan’s nuclear policy.

Assessment of Reforms

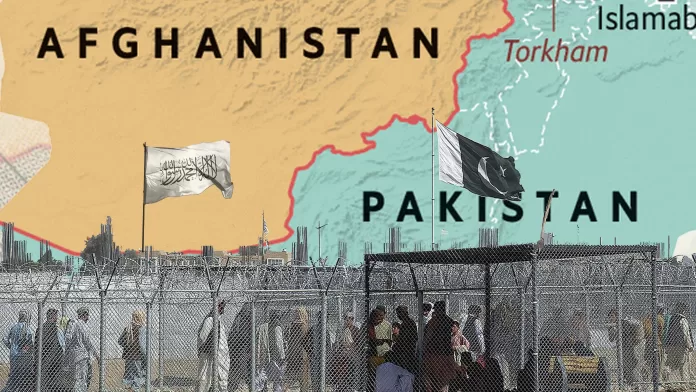

Reforming Pakistan’s HDO, particularly the CJCSC office, has long been debated. Proposals to transform the CJCSC into an empowered Chief of Defence Staff were examined in earlier staff studies. Today, Pakistan’s military operates across a broad conflict spectrum i.e., from counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism to conventional duels, air power, and long-range precision strikes. In the past six months, Pakistan has faced a confrontation with India and a duel with Afghanistan, while the army and air force remain engaged in counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency operations. These diverse engagements demand swift, integrated decision-making, efficient resource mobilisation, and coherent procurement. Transitioning from service-centric HQs to an empowered CDF HQ reflects evolutionary change, though cultural shifts within the military remain gradual. India’s experience shows that jointness is complex and often complicated by inter-services rivalries. In Pakistan, land forces’ dominance has the potential to spearhead an accelerated implementation. The first step came in January 2025 with joint cadet training i.e., an entry-level collaboration preceding current apex-level restructuring.

The recent higher defence restructuring marks the most significant shift in five decades. This change reflects operational realities i.e., multi-domain engagements, resource constraints, and the need for integrated planning. Proponents view it as a step toward synergy and efficiency, centralising strategy and procurement under a unified command. Critics, however, warn of excessive concentration of authority within the COAS-CDF, risking inter-service imbalance and reinforcing the military’s political dominance. Sustainability will hinge on institutional safeguards, such as a vibrant inter-services representation at the CDF HQs, along with separating CDF and COAS roles. Th next step for Pakistan would be to set up combined commands in specialised areas, such as cyber, aerospace and special operations to align with global trends. For now, the success of this reform will depend on its ability to deliver operational coherence without deepening structural asymmetries within the military’s own higher organizational system.