Shared interests have long been a factor in international relations, drawing countries closer together. However, practical demands take precedence over rhetorical affinities in the contemporary multipolar world, where power is more dispersed and competition is more complicated. Considering this, Pakistan and the United States (US) have identified areas of shared interest and cooperation. Following the US President Donald Trump’s second inauguration, what once appeared to be encouraging signs in the counterterrorism space now seem to be developing into a possible collaboration. Washington’s rekindled interest in Islamabad is the result of real progress. This revitalised partnership revolves around resources, trade, and security rather than idealistic and moralistic rhetoric.

According to strategic realism, states are logical actors that maximise their security and power in an anarchic international environment. Regardless of intangible benefits like ideology and sentiment, cooperation occurs when there is an alignment of the state’s essential interests. However, in global politics, rhetoric conceals the real calculations by presenting connections as morals and ideals. Rhetorical partnerships are, however, less about actual policy alignment or resource sharing and more about diplomatic and symbolic signalling.

It is interesting to note that President Trump’s foreign policy style has been transactional, with dollars, leverage, and hard power as the driving forces. Unlike his predecessors, who would emphasise norms, values, and moral underpinnings in making international engagements, the Trump administration’s policies mark a further shift, reflecting the distinct imprint of President Trump’s personality. As observed by Edward Frantz, a US historian, Trump, a baby boomer and football fan, seems inspired in his foreign policymaking by the ethos of legendary pro football coach Vince Lombardi, who famously said, winning is not everything, it is the only thing.

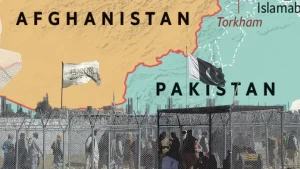

Pakistan appears to have adopted the transactional diplomatic style of the Trump administration by presenting itself as a partner that delivers. For instance, Islamabad facilitated the arrest of IS-Khorasan operatives, who allegedly masterminded the 2021 Kabul Airport attack that killed 13 US personnel. Before this high-profile capture, senior officials of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), a US government agency dealing with foreign intelligence and national security, and its Pakistani counterpart Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), were reportedly in contact with each other. This tangible delivery brought praise from President Donald Trump who admired Pakistan saying ‘I want to thank especially the government of Pakistan for helping arrest this monster.’ The appreciation was widely projected as this was conveyed by Trump in his annual union speech.

Nothing captures the shift from rhetoric to strategic realism than the economic basis of the new US-Pakistan engagement. Islamabad’s untapped reserves, oil, gas, rare earth, and critical minerals in Gilgit-Baltistan and Balochistan drew President Trump’s attention, reaffirming the pursuit of tangible and material interests. For Washington, these resources carry strategic weight: regarding energy diversification, bolstering supply chains in competition with China, and securing materials vital to high-tech industries. Moreover, Pakistan has signalled that its financial system is open to innovation, from welcoming US investment to exploring digital assets and cryptocurrencies. Islamabad has entered into a contract with World Liberty Financial, a company in which the Trump family holds a 60% ownership stake.

Strategic realism also explains why Pakistan’s moment has come at a time when Washington’s patience with New Delhi is wearing thin. India’s refusal to lower tariffs, its continued purchase of Russian Oil, and its continued refusal to credit Trump for defusing South Asian tensions have strained what was called a natural partnership between Washington and New Delhi. In this environment, Pakistan’s ability to secure a trade deal with the US, which lowered tariffs from 29% to 19% on Pakistani goods, has allowed Washington to reassess its South Asia policy, where Pakistan has traditionally been viewed primarily through a security lens. For Pakistan, it is more about occupying the space left open by India’s intransigence and converting it into tangible diplomatic and economic gains than gaining rhetorical points.

Strategic realism offers how Islamabad can utilise its ties with the US to alleviate its domestic problems in a rational bargain. For Islamabad, an unstable economy and terrorism remain primary domestic issues to address. The opening to US companies in rare earth minerals, mining, crypto, and oil and gas will bring Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), which will facilitate a conducive environment for the local market to develop. As counterterrorism operations are concerned, Pakistan and the US have been engaged in sharing intelligence and joint operations, especially after 9/11. For instance, fusion cells were created in Islamabad and Peshawar, enabling ISI and CIA officers to share satellite imagery, communications, and translation in real time, which helped capture terrorists. In the current scenario, Pakistan can integrate its newly formed National Intelligence Fusion and Threat Assessment Centre (NIFTAC) with US surveillance and financial tools to counter terrorism, especially around the mining routes. This would serve the core interests of both states.

In the emerging multipolar world, where no single superpower can dictate outcomes, Pakistan can maximise its interests. Islamabad can best manage its ties with the US, China, Iran, and BRICS, a forum of leading emerging economies, by pursuing a strategic realism that focuses on hedging and issue-based cooperation. It should keep China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Phase 2 focused on industrial zones and mining services with China, while ensuring security and transparency to attract sustainable investment. Iran should be engaged pragmatically, as evident in the latest agreements on the trade and energy sectors during the Iranian president’s visit to Pakistan. However, the gas pipeline project must wait for the US sanctions waivers to avoid blowback. To sum up, strategic realism offers much to satisfy Pakistan’s core interests without alienating its allies. The current US-Pakistan partnership fulfils the tangible needs of both states. Unlike the intangible and symbolic political partnership of rhetoric, which may have been useful in the past, the contemporary leadership, especially of the US, prefers tangible deliveries. It is high time for Islamabad to utilise its untapped resources and potential to garner benefits, while avoiding contemporary global issues such as the US-China confrontation.